In the fall of 2016, two friends and I embarked on an ambitious adventure in the Himalayas and attempted to climb two unclimbed peaks named after Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay – the first two men to summit Mt. Everest.

Elia Saikaly

After his mentor’s tragic passing on Mt. Everest, Elia, who had never climbed a mountain or even slept in a tent, decided to retrace his footsteps up the world’s tallest mountain. It was a decision that changed Elia forever. He is now an award-winning, high-altitude filmmaker, philanthropist, inspirational speaker and global adventurer. Elia has been to the top of Mt. Everest twice, participated in eight Himalayan climbs, and has scaled five of the world’s seven summits.

Pasang Kaji Sherpa

Pasang-Kaji isn’t your typical Sherpa. He’s a businessman, entrepreneur, expert climber, and father. When not climbing as a high-altitude Sherpa, he is running his climbing shop, and restaurant.

Pasang was recently in Syria helping civilians who were caught in the war. Risking his own life and his safety to help others seems to be a common occurrence for him. He is the ultimate Sherpa.

Gabriel Filippi

With over twenty Himalayan expeditions under his belt, including five on Mt. Everest, Gabriel is the only Quebecer and second Canadian to summit Everest from both the North and South side. He’s climbed six of the seven summits, led a heart transplant recipient to the top of Mt. Blanc and climbed numerous technical peaks in South America.

When not leading expeditions to the world’s tallest peaks, Gabriel shares his stories as an inspirational speaker to help others find success.

Travis Wood

Travis Wood – ie: Master of all trades storytelling and video production. Travis wore all hats on Unclimbed from director to producer to editor and director of photography. He shaped the promos, constructed the storylines in the edit suite and lead the charge in the field with his trusted crew and team from Bell Media and his sidekick and partner Graham Garside.

Graham Garside

Graham Garside is the other technical/creative half of Unclimbed – Reaching the Summit. Whether flying the gimbal, shooting camera, cutting French web-episodes or the 1 hr French broadcast on RDS, he had his talented hands in it all. Graham (also known as GG) typically works on all aspects of content creation, as producer, creative director, director and editor.

-

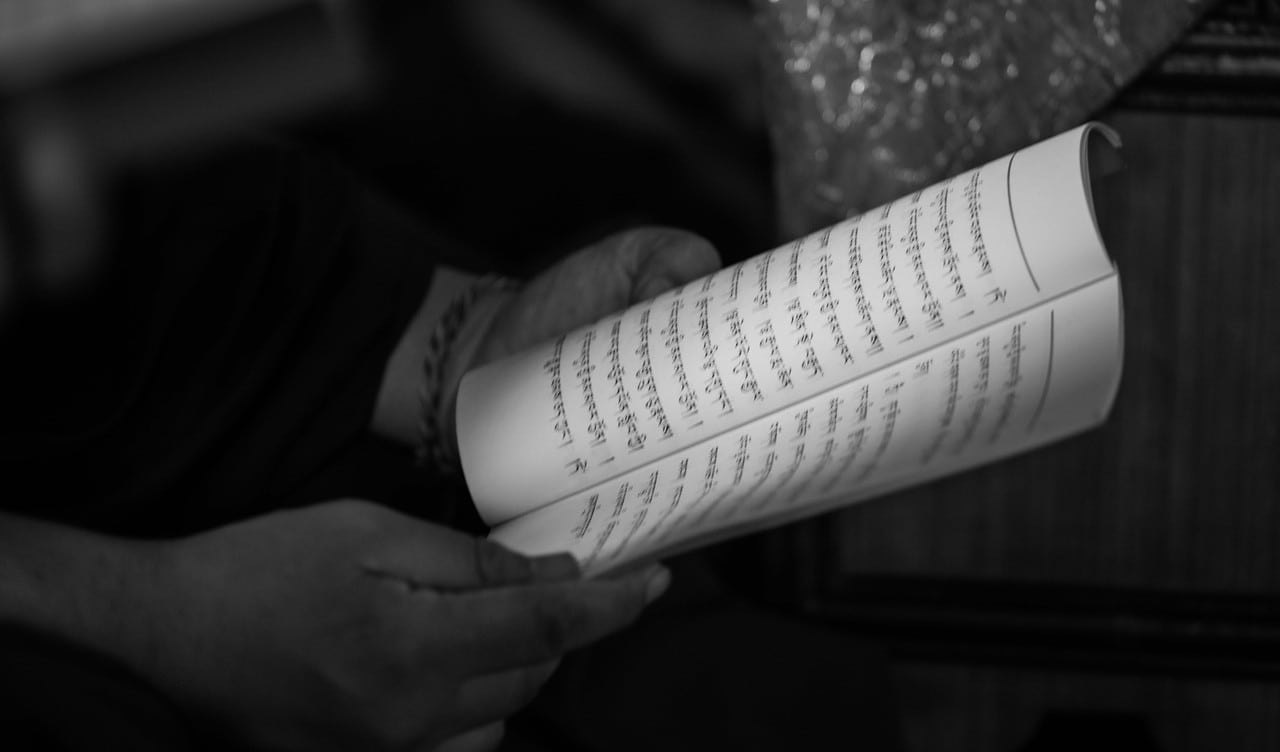

We shared the morning with Miss Elizabeth Hawley, also known as the 'Mountain Keeper' and creator of the Himalayan Database.

-

Test Caption

-

Another Caption

Inbound

Amazing treatment from Qatar Airways who sponsored our flights and graciously put us and the film crew up in business class with our 400+kg of climbing and film equipment. There will be plenty of suffering later, for now the comfort is incredibly well received and very much appreciated.

Testing gear on the roof of the Dalail La Hotel in Kathmandu - This is the gear that will keep us connected throughout the expedition. - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Testing Gear

Testing gear on the roof of the Dalail La Hotel in Kathmandu - This is the gear that will keep us connected throughout the expedition.

Streets of Thamel

The traditional densely populated streets of Thamel are much quieter than usual as the upcoming climbing season is still a few weeks away. We've been taking unnecessary rickshaw rides to help put a few dollars in the pockets of the local drivers who claim that business hasn't been the same since the 2015 Earthquake.

The Mountain Keeper

We shared the morning with Miss Elizabeth Hawley, also known as the 'Mountain Keeper' and creator of the Himalayan Database, the best-known chronicle of Himalayan expeditions for over four decades.

Puja Ceremony

For me, the Puja ceremony is the most beautiful part of Himalayan expeditions. We honour and respect the cultural beliefs and embrace the blessings and requests for safe passing in the mountains. The Puja marks the official beginning of our expedition.

Lukla to Phakding

Yesterday we landed in Lukla and were thrilled to see that our 1000+kg’s of gear arrived safely. The reality of this expedition is quickly setting in. There could be no better scenario to live out a dream with two of your closest friends.

Approaching the Mountain

Hard working, resilient, cheerful and always happy. Sharing the approach with these amazing human beings is one of my favorite parts of mountaineering expeditions.

Solu Khumbu

Moody landscapes in the Solu Khumbu.

Double suspension bridge on the way to Namche - Gabriel Filippi, Pasang Kaji Sherpa and Elia Saikaly - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Bridge to Namche

In approx 10 days we are truly going to be living and surviving on our own little planet with no one around for almost 50 days. This is PK Gab and I crossing the highest suspension bridge in the Khumbu Valley.

White Out

Yesterday morning it looked like this, which is outstanding. This morning we are departing in a complete white out. We've got 10 hours or so ahead of us before reaching the next destination.

Keeping things light on the approach - @GabrielFilippi @PasangKajiSherpa @EliaSaikaly - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Dreams becoming

I've learned that any dream worth dreaming is the dream with the uncertain outcome.

A Team of Three

No, he's not our climbing Sherpa. No, he's not here to carry loads or my camera gear. No, we did not receive a discount on his fees because he's Sherpa. He's on our team. One of three. Equal contributor in planning this every step of the way. We're all in this together.

Stunning morning views in Machermo with our new friend Lobsang - owner of the lodge we stayed in. - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Machermo

Stunning morning views in Machermo with our new friend Lobsang - owner of the lodge we stayed in

My Favourite

These guys, my absolute favourite part of Nepal and the Himalayas.

In my element

Me in my element, gearing up for what’s to come.

Sonam Sherpa

This morning Sonam and I hiked up to the top of Gokyo-Ri at 430am at 5300m, to capture some sunrise imagery of the surrounding peaks. To my surprise after asking him a few questions about his life, he shared a very sad story of both of his parents dying far too young. One by 'disease', the other a construction accident. He and his older sister take care of their younger sisters who are still in school. Working as a porter is his main source of income. The sad truth: he only does it for the money. To provide for his sisters. Imagine that responsibility at 19 years old.

Everything We Need to Survive

Alright my friends, this is it. From here on out it's Gab, PK and I, 1000kg's of everything we need to survive, a herd of yaks, a team of porters, a few great Sherpas and one hell of an unknown adventure for the next 60 days.

Unchartered Territory

We've officially entered Unchartered territory and established Hillary Basecamp just over 5200m above sea level.

Recon

Recon has begun as we attempt to unlock the route to the upper part of the mountain.

Opening the route to access the upper part of the mountain #Unclimbed - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Unlocking the route

Gabriel Opening up the route to unlock the upper part of the mountain

Immense Challenges

Today, we are challenged immensely by circumstances beyond our control. The outcome is uncertain and danger lies at every turn. The unknown route is humbling and damn right intimidating. In the face of hardship and adversity, we revert back to our core: to dare to dream and risk to venture for the love of exploration with the high risk of failure and potential for a monumental shared experience between soul brothers born worlds apart. We wanted a challenge, well here it is. An opportunity to soar or crumble. This is the field of all possibility. And I honestly have no idea which way this is all going to work out.

A team of two

And then there were two… Two weeks ago I watched in sheer horror as my best friend and climbing partner Gabriel flew off the cliff he was scaling, upside-down and backwards to what I was certain would be paralysis or death. He bounced uncontrollably like a rag doll, over 60ft, from cliff to cliff, before eventually coming to a stop just feet next to where PK was belaying him. In total shock, I ran down to his aid praying for the best, terrified of the worst possible outcome.

Our Puja at Hillary and Tenzing basecamp #Unclimbed #FindingLife - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Puja in 360

Our Puja at Hillary and Tenzing basecamp

Heading back to basecamp alone to meet Pasang Kaji Sherpa - Photo in Phakding - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Return to basecamp

Heading back to basecamp alone to meet Pasang Kaji Sherpa - Photo in Phakding

Pasang Kaji Sherpa at Gokyo lake - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Gokyo Ri

Pasang Kaji taking a little hike and solo’ing Gokyo Ri

Heroes of the Himalayas

17 days ago these incredible men built a helicopter landing pad with their bare hands so Gabriel could be evacuated to safety down below. At 5200m, this is an incredible display of care, love and strength. Today we return to where it all happened and commence the journey. We carry on with the dream that was halted and almost came to an end.

Best lodge in Gokyo - Meet Kami the owner and Kusang PK's nephew #Unclimbed #FindingLife - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Kami’s Lodge

Best lodge in Gokyo - Meet Kami the owner and Kusang PK's nephew

Scouting the lines outside of basecamp #unclimbed - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

Scouting the lines

Scouting the lines just outside of Hillary Basecamp

The Puja

Pasang Kaji raised the prayer flags as Dangima, one of our porters, led the ceremony in prayer. We had our gear and personal belongings blessed which included photographs of our loved ones. The weather Gods were very kind to us and graced us with crystal clear skies.

The South Face

The south face of Cho Oyu lit up by the rising moon with an appearance by the glorious Milky Way.

Ice Wall

At 4am, we rise and begin our journey around the deadly icefall in search of a new route. After 6 hrs of breaking trail and forging a path up to 5900m, we were met with this giant ice wall.

Passing the torch

There is a fire in Pasang Kaji’s eyes that I’ve never seen before. He’s truly stepped up and today I graciously passed on the expedition leader torch and placed it in his hands. We work as equals, but should we succeed, it’s important to me that he be recognized officially as having stood in the forefront.

Our story

We just had egg fried rice for lunch and deep fried spring rolls. In the distance, we can hear avalanches which are a common occurrence here in the Himalayas. We know they’re too far away to affect us, nonetheless, I never quite get used to them. After getting hit by last year’s avalanche on Mt. Everest, I’m always prepared to run when I hear one, even in the middle of the night. Water can be heard flowing beneath us as we are camped out on the largest glacier in Nepal and it’s constantly melting and shifting. It’s relatively warm at the moment, approx 12 degrees celsius, but by 4pm, we’ll need to bundle up in our down jackets and pants as the temperature dips drastically as the day turns to night. This is a slice of our lives on a rest day in the high mountains of Nepal.

I decided to start this blog for one reason: because of you. I learned that a group of students have been passionately following our adventure. Not only have they been following, they’ve been actively helping us reach our goal. How you ask? They’re using our GPS positions and the latest satellite data and imagery to track our progress, map the route ahead and make suggestions on which direction to climb. You see, very few people have ever been up here and according to the Nepal Government, no one has ever climbed these two mountains. So it’s unchartered territory, which means it’s unmapped and there is very little information for us to build a plan upon. We don’t know which way to go and so each time we try to climb, it’s trial and error. Sometimes we go the wrong way and spend an enormous amount of energy only to reach a dead-end. Other times, we are successful and make great progress in what we call “opening up the route’, which means we create a path where there isn’t one, usually in deep snow, and put in safety lines incase we fall.

If you’re learning about our expedition for the time, then let me give you a summary of where we are at.Our dream began as three friends: myself, Elia Saikaly, my closest friend Gabriel Filippi and my dear Sherpa friend, Pasang Kaji Sherpa. We left our families behind in August and embarked on this grand adventure. Our goal? To attempt to summit two mountains in Nepal named after Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay – the first two men to successfully climb Mt. Everest. Everything was going according to plan and then on our first-day climbing, Gabriel had a terrible accident and almost lost his life. Passing Kaji and I rescued him and he was evacuated to Kathmandu. After knowing he was going to be okay, after suffering minor injuries, Pasang Kaji and I (or PK as he likes to be called) decided to keep the dream alive and we returned to the mountain and refused to give up.

So here we are, almost 8 weeks later, at the base of Hillary and Tenzing basecamp and we’re waiting for better weather to climb. The Monsoon season in Nepal (the rainy season) has been very unkind to us. It’s been raining and snowing for weeks. This makes our job incredibly difficult as rain down low means snow up high where it’s much colder. Our current goal is to finish opening the route to camp 1 around 6100m above sea level. If we can achieve this, we will have accomplished a huge goal. While still far from the summit, it would be one giant step closer to accomplishing our dream. After all, you can’t climb a mountain in a single day, it’s all about taking one step at a time and slowly and safely reaching your goal.I hope you will join us on this adventure. It’s ben tremendously difficult so far and it’s certainly not going to get any easier, but we are resilient, we are determined and we keep the purpose of our dream alive and that gives us strength. Also, knowing there are so many of you joining us on the journey fuels us and gives us extra motivation to work even harder and forge a path upwards towards our goal.<

We look forward to sharing our adventure with all of you!

Together we climb

He bounced uncontrollably like a rag doll, over 60ft, from cliff to cliff, before eventually coming to a stop just feet next to where the third member of our team, Pasang Kaji Sherpa, was belaying him. In total shock, I ran down to his aid praying for the best, yet terrified of the worst possible outcome.

Miraculously, Gabriel survived. He escaped death. We spent nearly 30 mins helping him orient himself as he had no idea where we were or what we were doing in Nepal. He was alive, but we needed to get him down to safety.

Pasang Kaji Sherpa and I went into rescue mode, belayed and short roped Gab down to safety, 500m below -a Herculean effort to cut and kick steps in the thin 5700m air, for one tumble could potentially escalate the miracle on hand into a code red evacuation. Miraculously again, Gab was able to stand on his own, demonstrating an incredible will to survive.

In short, we evacuated Gab. The following morning, the incredible porters working with us at basecamp built a helicopter landing pad with their bare hands and we got Gab on the chopper down to safety in Kathmandu.

It’s been quite the emotional roller coaster ride since the accident. The priority was and always has been Gab’s safety and well-being. He is now home, almost unscathed, with a severe concussion and the tale of a fall that would have killed most climbers.

We came to Nepal to live a dream and for many days, that dream was over. Our mission was to attempt scale two mountains recently re-named in honour of Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, the first two men to successfully climb Mt. Everest. According to the Nepalese Government, both summits are unclimbed.

For those who aren’t alpinists, allow me to break things down a little for you. We live in the age of commercial climbing expeditions. As illustrated in the recent ‘Everest, Hollywood film, based on the best-selling book ‘Into Thin Air’, clients who aspire to climb Mt. Everest can dish out $65,000 for a spot on an expedition. There are traditionally hundreds of Sherpas working on the mountain. The path is broken, the safety lines are put in place, the tents, the camps, the food and the water is traditionally 100{c0d616ec23a1ea78237269fee999fd3e756e1235669a36003e38faaff0a7a27b} taken care of by hired guides and climbing Sherpas. The route is known and there is a certain level of rescue support should anything go wrong.

In the spirit of adventure, we decided that we would steer away from the classic Himalayan climbs and set out on our own as a small three man climbing team. We hired a minimal team of porters to help us establish basecamp at 5200m. We’re carrying everything ourselves that we need to survive including 2000m of safety lines, ice screws, snow pickets, biners, stoves, gas and personal climbing gear, not to mention a whole whack of camera gear as my other responsibility is to film and photograph this climb every step of the way. Why you ask?

For me, this project was and is about Pasang Kaji Sherpa. A man I’ve built an unbreakable bond with over the past 4 years on Himalayan expeditions. We’ve stood on top of the world together and survived two devastating avalanches on Mt. Everest, in 2014 and 2015. It was clear to me that the first to attempt, and possibly succeed, on these two peaks should be a Sherpa. These are after all their mountains and Nepal is their beautiful country. After so much hardship in the high Himalayas over the past few years, combined with the reality of being wrongfully cast in the shadows, we wanted to enable Pasang Kaji and help him climb from the shadows into the limelight where he and his Sherpa brothers belong. Not as load carriers, but as leaders.

The evening we rescued Gabriel, Pasang Kaji Sherpa welled up in front of me, an uncommon act for a Sherpa, and asked me: Why we going down? Why we don’t try? Gabriel is okay? Torn between right and wrong under extreme duress and uncontrollable circumstances, I decided to listen. I was so caught up with the evacuation that I failed to consider the feelings and the ambition of my dear Sherpa friend. I decided in that moment that I would try to salvage this expedition, ascend as high as we can, as two friends with our team leader’s spirit with us.

It’s been a near-impossible feat trying to reinstate this expedition, but after 19 days of hardship, which includes flying to Kathmandu to support Gabriel to be by his side, only to turn around and return to the Himalayas, walk 55km uphill to basecamp in the rain, turn the yaks and porters around so we could make a proper attempt, we are finally back at Mt. Hillary and Tenzing basecamp.

Will we make it? We have no idea. But our spirits are strong and our hearts are in the right place. Pasang Kaji and I will climb as high as the mountain Gods will allow us. It’s more dangerous than its ever been at this point as we are down our team leader. We both have loved ones and families back home that are supporting us every step of the way. Nothing would be more incredible than to see Pasang Kaji stand up there first as a Sherpa, symbolically, for his people, as a leader, at the forefront, where I believe he and his Sherpa brothers belong.

Deepest of breaths as the outcome is now the most uncertain it’s ever been. Together we

Up the couloir

As we made our way up the couloir, to the point where Gab had his accident, I couldn’t help but feel anxious and wonder: will the same thing happen to one of us? "Are you nervous?" I asked PK “Nope” he replied. “I’m excited to climb”. We forged a path to the left and found ourselves buried in snow up to our waists for the next 7 hours. Every vertical step was three times the effort it should have been as we’d penetrate the top layer of snow and repeatedly sink. At altitude, this is no small task.

Unlocking the route

You see, the Sherpas believe Gods inhabit these peaks and before climbing one must pay deep respect to the mountains and offer gifts and good intentions in exchange for safe passage. I deeply respect their beliefs (as I do all cultural beliefs) and approach the burning juniper at the base of the altar. I scoop up a small handful of rice in my right hand, bring my hand to my heart and toss the rice in the air and humbly ask for safe passage.

At 5am, after an hour of climbing we find ourselves at the first resting point. There is a fire in Pasang Kaji’s eyes that I’ve never seen before. He’s truly stepped up since we lost our team leader. I graciously pass on the expedition leader torch and place it in his hands. We work as equals, but should we succeed, it’s important to me that he be recognized officially as having stood in the forefront where he and his Sherpa brothers belong.

Pasang Kaji’s story continues to marvel me as I peel back and uncover the layers of how far he’s come in his life. He’s emerged from a family line that wed his parents at the age of nine and twelve. From incredibly humble beginnings, a village few have ever heard of, where most children in the area don’t go to school and the average income is less than a dollar a day, to standing here: shining as a leader, businessman, father, certified guide and friend. I can’t help but smile and be proud that I’m a part of HIS journey.

As we made our way up the couloir, to the point where Gab had his accident, I couldn’t help but feel anxious and wonder: will the same thing happen to one of us?

“Are you nervous?” I asked PK

“Nope” he replied. “I’m excited to climb”.

We forged a path to the left and found ourselves buried in snow up to our waists for the next 7 hours. Every vertical step was three times the effort it should have been as we’d penetrate the top layer of snow and repeatedly sink. At altitude, this is no small task. With two ice axes in our hands, we climbed in mixed terrain, leveraging the ice, the rock, the snow and fixed the route using ice screws, snow pickets and hundreds of feet of Korean rope. With deadly seracs looming ominously overhead, the common theme was: one mistake will cost me my life. I found focus within and felt my way through, front pointing my way through the difficult sections with four points of steel connected to mountain. Heart beating steadily, endorphins flowing freely, for hours we climbed and achieved a new high point, just 200m beneath our proposed camp 1.

“What do you think,” I ask PK.

“Do we go left or right?”

Option 1 is likely an ice wall we need to climb with dead end littered with invisible crevasses and Option 2 may unlock the route to upper half of the mountain. Or it might not.

We decide to descend due to the deteriorating weather. This is a huge accomplishment for us and we now know we are just 200m beneath Camp 1 which gives us access to the upper part of the mountain.

The suffering is immense, but the joy of being in the mountains, connected in nature, bonded and bound by a brotherhood, outweighs the temporary inconvenience of pain and discomfort. “This too shall pass”. My mantra for everything difficult in life.

Uncertainty awakens the soul and unlocks potential un-imagined. All is unwritten and we can’t wait to live what happens next…

The Mountain

Alone, connected to the mountain, in tune with nature, lost in flow and nowhere to be but immersed deep in the present moment.

Living on the edge

I look up and see a giant overhanging serac that could crush us in the night. I then look down and see a 65 degree slope which leads into the abyss. Rather than focus on what could go wrong, the three of us continue working together as a team to make things right.

I’m clipped into an anchor via a safety line as is Psang Kaji and Kusang. We’re all exhausted from the climb, but manage to compartmentalize the pain, ignore the cold and carry on chopping ice. PK and I manage to set up the tent ignoring the danger above and below us. Meanwhile, Kusang down climbs to the previous anchor in the dark to collect our backpacks that are half buried in snow and attached to a separate anchor.

“This is insane”, I mutter under my breath. The irony is that when I check in with myself, as I often do, I can feel that my soul is incredibly alive. My endorphins are flowing creating this incredible rush that can only be described as the ultimate feeling of “alive”. As challenging as the circumstances are, I’m thrilled to be free-flowing and immersed deep in the now. There is no time to think and no time to worry. There is only time to take action.

Before we know it, the three of us are squeezed into a small North Face tent. The edge of the tent overhangs the cliff and we all decide that rather than attempt to sleep horizontally, we’re going to sleep partially upright against the rear wall so as to not fall off the side of the mountain during the night. PK secured the tent to the ten thousand year old ice using three ice crews. The greatest danger is the serac above us. We are completely at the mercy of chance at this point, which is a position neither of us is happy about. There are some risks you can control and others you must leave to fate. Only in extreme cases like this one do we rely on ‘good luck’ to get us through the night.

I unroll the mats, blow up the sleeping pads, unpack the sleeping bags and dive into my down suit. I quickly transform from freezing to toasty warm. We make hot water using a portable stove and the ice we chopped and feast on Happy Yak dehydrated meal packs. Shepherds Pie for me and Cous Cous for PK and Kusang.

Our clothes are soaking wet from the climb. With no other way to dry them, we take our jackets and pants and shove them down the neck of our sleeping bags. My socks and gloves and placed down my pants and inside my shirt against my skin in order to have a chance at climbing the next day with warm clothes. It’s unbearably uncomfortable, but the warmth of our bodies is the only hope we have to avoid freezing during the climb the next day.

It’s an unbelievably sleepless night. The common occurring avalanches seem all too close and I can’t help but pray that the giant house size block of ice above our heads doesn’t collapse and crush us while we sleep. I drift in and out of a light sleep as snow continually slides down the vertical slope pounding my side of the tent. I’m officially at the mercy of the mountain and do my best to fall asleep and wait for morning.

High altitude critical thinking

It would be easy to feel deflated or defeated after this last rotation. After all, we risked our lives sleeping on the exposed ledge we carved out on the side of the mountain with our ice axes. Rather than see it all as a failure, we choose to be optimists and see it as a success. We endured extreme hardship and climbed as high as we could before concluding that there was no way to access camp one from where we were. Even if we would have continued on and scaled the 90-degree ice wall that Pasang Kaji scouted when he disappeared from my view, there was no guarantee we would reach the plateau that is the gateway to the upper part of the mountain.

Initially when this project was conceived, the plan was to show up at the bottom of the mountain and figure it all out on the spot without any assistive technology. While I admired this pioneering spirit, being the tech geek and filmmaker that I am, I argued that it would be foolish not to use the modern day tools accessible to us to help us plot a safe path to the summit.

Below, you can see some of the 3D satellite images that we’ve been using to get to navigate the unclimbed terrain. Our friends at ESRI have put together an incredible 3D map and have even marked the summits using the GPS points we provided them with. In addition, we’ve been using binoculars, special cameras provided by Canon Canada with impressive digital zoom capabilities and high resolution DSLR cameras that I use to photograph the mountains from a distance which we then load into my laptop and study.

Our original plan was to scale these two unclimbed peaks as a three-man team. After Gabriel’s accident and evacuation, combined with the time it took to get him down to safety, the 55km trek back to basecamp, the turning of the yaks around and carrying all the gear back to basecamp, we lost three weeks of climbing. At a serious disadvantage, all of a sudden students like you stepped up and began studying the satellite imagery and proposing climbing routes. In addition, a perfect stranger that we’ve never met named Louis Rousseau, another profession climber, also began sending us route options using satellite imagery and 3D maps. We feel as though we now have an extended virtual team all working together to help us access the upper part of the mountain. We’re incredibly grateful for the support – the power of teamwork!

As of today, taking everyone’s suggestions into consideration, given the Monsoon weather and the ticking clock on our climbing permit which expires on Oct 14th, we’ve concluded that we have one option left. It’s an option that we have been avoiding since day one because of how dangerous it is.

To the right of basecamp, there is an unstable icefall that is collapsing and shifting daily. As we sleep, we hear the constant sound avalanches and the roar of thunderous rock fall coming from that area. It was a path that was momentarily considered early on, but then quickly discarded due to the extremely high level of risk. At this point, PK and I have concluded that it’s the only option we have left.

We’re going to sleep on it, carefully consider the risk vs. reward scenario and make a decision as soon as possible. If you were in our boots, what would you do?

For now, we’re recovering from the last rotation, filling up on Dhal Baht (rice and lentils) and getting some well deserved rest before making the most important decision on this expedition.

Much love,

Elia and PK

Our expedition is over

The Monsoon season has been relentless, one of the longest the locals have seen in ages. We could push on and force our way up the mountain, but the reality is that it’s only going to become more dangerous as we climb higher. Buried crevasses invisible to the eye between camp one and two are but our first set of concerns. Beyond camp one and two, we would then have to deal with a ticking clock, deep snow and unpredictable avalanches higher up.

The only viable option we had left is a route to the right of basecamp to the left of the icefall. This is a route that was momentarily considered early on, then quickly discarded due to hazardous of rockfall from hundreds of feet above and daily avalanches that litter debris at the entry point of the route.

PK and I deliberated for days and have now determined that it simply isn’t worth the risk. Neither of us is willing to lose our lives to reach the summit.

Given the intention of this resurrected climb, which was to see Pasang Kaji stand on top of Hillary Peak first, I decided to place the final decision in his hands. I was prepared to dance with the mountain one last time should that be his decision, but I was also very ready to back down pending his wishes. I asked him: “What do you want to do? It’s all in your hands, my friend”.

“Risk is too high”, he said.

“It’s like 100 times risk”.

My heart sunk, but I deeply respected his decision. And just like that… it was all over.

One requires far more courage to accept defeat than than to carry on upwards, blinded by ambition. Thankfully I learned this lesson many years ago on Mt. Everest.

The weeks spent putting this expedition back together after Gab’s accident were extremely stressful. Not only on PK and I, but on our families back home and on the porters and staff who had to reverse all of their teardown efforts. I worked as hard as I did to put this expedition back together because I wanted PK to have a shot at seeing this project through. It was important to me that he be given a chance to climb as high as he could climb. I’m so incredibly proud of how he led, took charge of the expedition and masterfully opened up every line we chose. I hope his star continues to rise.

I know in my heart that we made the right decision. Neither of us are prepared to die on a mountain and ruin the lives of the people we both love. We’re both here today because we’ve always known when to back down.

We gave it our best shot, we poured our hearts into this, but unfortunately the heavy odds stacked against us prevailed. We walk away knowing we fought with everything we had, we were relentless, resilient and took the humble approach in the end of bowing out gracefully and accepting that the mountains simply don’t want to be climbed at this moment.

Your prayers, support, comments and best wishes have meant the world to us. Thank you for embarking on this incredible adventure with us. It’s been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life.

We’re on our way back to Kathmandu for a well earned shower and an uninterrupted call home to reconnect with our loved ones.

Much love,

Elia and PK

The Unsung Heroes of Unclimbed

Sadly, they are often wrongfully omitted from the stories of triumph and success by foreign climbers and mainstream media. It’s important to remember that these big mountain expeditions, including ours, are not only dependent on the help of the Sherpas, but also other casts of men (and sometimes women) which includes porters who leave their families for months at a time to seek out employment. This blog post is a tribute to these great men.

In the case of our expedition, our porter team members traveled from Changa, a village in the Taksindu district. They walked for two days to meet us in Lukla. From there,1000kg’s of equipment was transported by yak to our rock camp at approximately 5000m above sea level. Many of our team members traveled with us helping transport our fragile film equipment and personal belongings. From there, the crew made multiple trips, oftentimes with double loads on their backs (only those that insisted, who wanted to earn extra money, carried double loads in excess of 40kg) to the end of the trail. From there, they descended a step rock trail and crossed the Zgozumba glacier, the largest glacier in Nepal and finally reached basecamp.

These porters work incredibly hard and develop this work ethic from a very young age. Honestly, I have no idea how they do it. They never complain, they’re generally always positive and are often singing and dancing along the trails.

Earlier in August, I had a chance to get to know Sonam, our youngest porter who is 22-years old. He’s tech savvy, funny, has a stylish haircut and can dance circles around me on a smart phone. To my surprise, after asking him a few questions about his life, he shared a very sad story of both of his parents dying far too young. One by ‘disease’, the other a construction accident. He and his older sister take care of their younger sisters who are still in school. Working as a porter is his main source of income. The sad truth is this: he only does it for the money. To provide for his sisters. Imagine that responsibility at 22-years old?

I share Sonam’s story as a gentle reminder to everyone to: 1) be grateful for what you have. Others are not always so fortunate. And: 2) Be curious and considerate of the people you meet in life. You never know where they come from, what they’ve been through and what additional weight they might be carrying.

Our porters: Sonam, Dorje, Dagnima, Baji and Pema have been extraordinary to work with. When Gabriel was evacuated back in September, we urgently needed a helicopter landing pad. Together, in less than an hour, they built one with their bare hands! They worked quickly and tirelessly, while Gabriel was on supplemental oxygen, moving rocks, paving the uneven ground while blistering their hands, and before we knew it, the helicopter landed and carried us away. It was one of the most extraordinary efforts I’ve even have the privilege of witnessing.

The other unsung hero of this expedition is my dear friend Dawa Sherpa, our cook. He has the most infectious smile and unique laugh that you’ll ever hear. He works hard every day in his red kitchen tent and creates all of our meals for us, often with extremely limited ingredients. A few days ago, he shared that he deeply misses his family. Due to extreme remote nature of this expedition, he thought many times of quitting and returning home. Like all of us, it’s extremely hard on Dawa being so far away from the people he loves the most. Thankfully, he decided to stay despite his longing for his loved ones.

After Gab’s evacuation, for a period of approximately seven days, our expedition was over. It took us some time as fends to conclude that the expedition should carry on. At the time, because the team at basecamp had no communication with us in Kathmandu, they began dismantling basecamp and carrying loads back to the rock camp at 5000m. Days later (keep in mind how heavy all the equipment in) they were then asked to return to basecamp with all the equipment. Naturally they were frustrated as they had spent days carrying hundreds of kilograms of equipment for nothing.

After trekking 50km’s back to rock camp, I met with the team and gave everyone the option to go home to their families. I explained that there was no expectation for them to carry on, but that we hoped they would support us. Regardless of their decision, they would all be tipped handsomely and paid in full. Everyone ended up staying to put the expedition back together.

PK and I may be at the forefront of much of our expedition stories and imagery, but it’s Dawa, Pema, Dorje, Sonam, Dagnima, Pema and Kusang who have earned their spot on our immediate and have become the real heroes of this expedition. We tip our hats off to them and thank them from the bottom of our hearts for all they have done. Their physical strength, unwavering dedication, open hearted nature and positive attitudes make them an example of the quality of character that we should all aspire towards