I’m honestly blown away at how many people have connected with my video, Everest — Time Lapse Short Film. My goal was to bring to life the majestic beauty of the Himalayas and draw attention away from the negativity that has surrounded Everest in the past years. I wanted to remind people of the infinite possibility that the tallest mountain on Earth symbolizes in each of us.

I was hired to shoot a television series called “Arabs on top of the world.” The story of the first Saudi Arabian woman, Qatari and Palestinian men to stand on top of the world. In parallel, I was partnered with www.epals.com and shared the journey in real-time with 800 classrooms across the world.

As a filmmaker shooting on Mt. Everest, I was incredibly challenged by the altitude, the cold, the lack of oxygen and the deteriorating nature of the environment. The higher you climb on an 8,000M peak like Everest, the more difficult it becomes to think, sleep, eat, function and survive. There is a reason why few come back with spectacular images and that’s because you’re literally dying up there and your priority is to remain alive.

In my case, to do what I do, my priority has to be my camera. It comes first. Everything else must become a reflex. It has taken years to learn how to mentally program my mind and body to be able to withstand the challenges associated with high altitude cinematography. In the death-zone, your body is deteriorating faster than it can recover and a simple mistake can mean the difference between life and death. It may sound overly-dramatic, but it’s the nature of the environment. Exposing your hands for too long leads to frostbite, failing to monitor and manage your energy can lead to inability to descend, failure to properly clip into a safety line while taking a shot can send you plummeting down the mountain to your death. These are but some of the risks you need to mange and all of this must become second nature if you’re going to operate a camera successfully and keep it and yourself alive.

Here’s a glimpse into the world above 8,000M above sea level:

It’s 9 p.m. and we’re at 8,000M above sea level on the world’s tallest mountain. The plan is to spend the next 24 hours in the death-zone ‘resting’ before pushing to the top of the world. The only thing keeping us alive is supplementary oxygen and the thin yellow tent walls that separate us from the frigid sub-zero temperatures. I’ve got seven cameras with me, over 30 batteries, a tripod and everything else I need to capture the magic of the Himalayan skies at night. It’s going to take an incredible amount of will power to rise, put my 8,000M boots on and set up the second last shot of my time-lapse — a rare scene of climbers leaving camp 4 making their way to the top of the world.

What gear did I use?

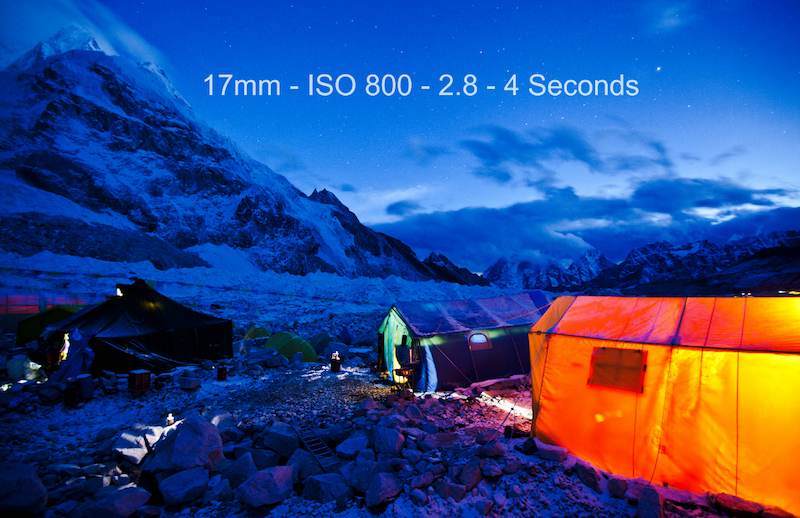

I was equipped with four Canon cameras: two 5D Mark II’s, a 7D and a t3i. I had three lenses with me ranging from 16mm-200mm focal lengths all with 2.8 apertures. I had over 30 batteries in total, six pre-charged solar batteries which were carried for redundancy and more hand warmers than one can imagine. I used four time-lapse remotes purchased from eBay and as much creativity as my oxygen deprived mind could conceive. If you can believe it, most of these shots in the time lapse film were set up within a few feet of my tent’s front door. I would set an alarm and wake up in the middle of the night, crawl out of my warm cocoon of a sleeping bag, pop my head out, glance up at the sky (usually in awe!) and I’d then shoot a few test frames to figure out my exposure, shutter speed, ISO and aperture. I’d then lock the tripod off and go back to sleep. Twenty-two hours later, I’d wake up again in the middle of the night and rather than shoot a few test frames I’d capture hundreds sometimes thousands of images at a time. Most nights, I could roughly estimate the path that the moon would travel and then adjust my framing accordingly to allow the moon to pass through the frame. It’s incredible to review the sequence in the morning and watch mother nature’s magic in action. The appearance of the Milky Way completely blew my mind! I really didn’t expect to capture it on camera. Here are some of the settings I used:

As an adventure filmmaker I am expending much more energy than most climbers which places an enormous amount of responsibility on my shoulders. If I get sick, I put everyone else at risk. As a precaution, I hired three Sherpas to assist me with oxygen, personal equipment and some of my camera gear. Without their help, this would not have been possible. What also made it all so incredibly challenging was the fact that I could not slow anyone down or interfere with anyone’s expedition, including my own team. I didn’t have the luxury of asking anyone to stop or wait or to repeat an action as you often do when shooting television. I needed to be 20 steps ahead of everyone else at any given moment at all all times which is a near-impossible task at 8,000+M. I honestly believe that it’s in the mind where you fail or success and I just had to be faster, stronger and even more resilient than the already driven climbers attempting Everest.

How did I assemble it all?

Every single image was processed in Adobe Lightroom on a Macbook Pro as high as 6,400M above sea level. Yes, I had an edit suite at 6,400M! I was powered by the sun and stayed warm at night thanks to a little heater that I named Wall-E. Once the images were batch processed I used Quicktime to compile image sequences into movies which were then edited together in Final Cut Pro. Approx 40,000 photos were compiled into 40 shots which I narrowed down to the best of the best. The result is what you see in the final film. The music was intuitively chosen as it often is in my work. I was surfing a website called AudioJungle.com and came across a track called “A Heartbeat Away.” The music conveyed the exact emotion I was hoping to evoke and I was 100 per cent certain it would accompany the images beautifully.

Elia